SLSA

“Software supply chain” is a term describing everything that happens to code from the time it leaves the developers fingers until it runs in production. The code needs to be compiled, tested, packaged and deployed, and these steps take place in a variety of systems and use lots of complex third party solutions. Our apps also depend on an increasing number of third party libraries and frameworks that we often know next to nothing about.

Every step in the supply chain represents a possible attack vector. If a malicious actor is able to compromise one or more parts of the chain it is trivial to inject any kind of malware into our products. Why use loads of resources trying to circumvent all the security measures in production when you can quietly insert all the backdoors you need beforehand? The steady rise in supply chain attacks show that more and more threat actors are embracing this way of doing business.

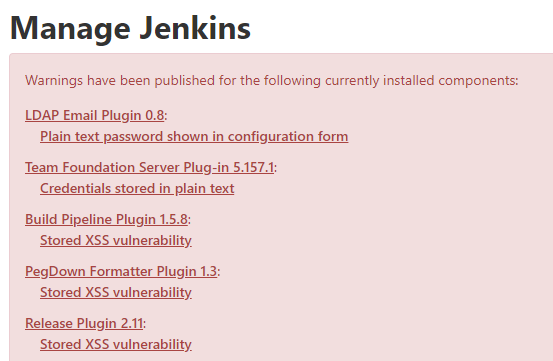

There are several steps we can take to maintain the integrity of our supply chains. The first and most obvious one is to put as much care into securing our build and development pipelines as we do our production environments. Anyone with a few years experience in this industry has seen far to many unpatched and misconfigured Jenkins servers loaded with crappy plugins that store secrets in plain text. Not that it makes a huge difference anyway since the same secrets are readily available in the company-wide Slack and haven’t been rotated in 5 years. 2FA, proper handling of secrets and configuration, regular patching, all that good stuff must also be applied to the dev side of the house.

Another step is actually knowing what it is that we put into production. When we ask someone to trust our software to handle their personal information and money we should at least be able to tell them what parts our products are made of and how they are put together. The U.S. government has already published an Executive Order that require their vendors to produce a “SBOM”, or “software bill of materials”, which is a list of components analogous to the list of ingredients on food packaging. Others are likely to follow suit.

Several initiatives have been started in an attempt to address the issues surrounding supply chain integrity, the most noticeable one being Supply chain Levels for Software Artifacts - SLSA. SLSA aims to be vendor neutral and is backed by major players like the Cloud Native Computing Foundation and Google in addition to startups such as Chainguard.

SLSA is “a security framework, a check-list of standards and controls to prevent tampering, improve integrity, and secure packages and infrastructure in your projects, businesses or enterprises”.

The framework defines four levels of increasing assurance defined by best practices:

| Level | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Documentation of the build process | Unsigned provenance |

| 2 | Tamper resistance of the build service | Hosted source/build, signed provenance |

| 3 | Extra resistance to specific threats | Security controls on host, non-falsifiable provenance |

| 4 | Highest levels of confidence and trust | Two-party review + hermetic builds |

Level 4 is not feasible for most organizations unless their software is powering missiles or nuclear reactors. Level 2 or 3, on the other hand, is very much achievable. The Kubernetes project is aiming for level 3-compliance in version 1.25.

A series of of tools and services to ease the implementations of frameworks like SLSA are also starting to appear. Cryptographic signing and verification is hard to do right, but the Sigstore project makes it a whole lot easier with their “Cosign” tool. Cosign can sign artifacts using ephemeral keys generated on the fly, or you can bring your own keys.

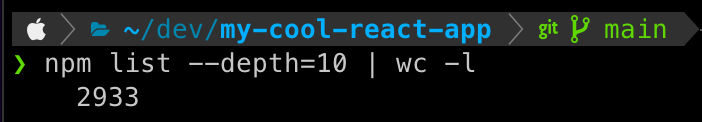

“Det skal være lett å gjøre det rett” (doing the right thing should be easy) is at the heart of our mission here at nais. We have therefore started to build some tooling to make it easier for any of our teams that want to dip their toes in salsa. The first iteration of this is a GitHub Action (currently in beta) that generates a provenance for the repo, signs it using Cosign and uploads it to the Docker registry. It can also be used to verify previously signed artifacts. The signing is done using our Google KMS. In order to create a provenance (which is basically the same as a SBOM) we need to figure out the dependency tree of the app. For that we currently support JVM-stuff (built with Maven or Gradle), JavaScript (built with npm or Yarn), Go (by parsing go.sum) and PHP with Composer (but without checksums). Other platforms may be added later should the need arise.

Since our builds are done using GitHub Workflows and the provenance is non-falsifiable (the action code and the signing key is controlled by someone other than the ones using the action) we are (semi-)confident that this solution satisfies level 3.

Now that we have the means to generate and sign provenances, what can we do with them? The short answer is: we don’t know yet 😀 The most obvious thing is compliance and building trust in our products. If at some point all of our teams start generating provenances we may introduce an admission hook to deny unsigned stuff in our clusters. We are also toying with the idea of uploading the provenances to some kind of data store so that we will have a complete overview of all the dependencies and the apps that use them. When the next Log4Shell comes along a complete overview of its usage is just a short query away. Another possible outcome is that we decide somewhere down the line that this whole SLSA thing is not useful at all and scrap the whole thing. Only time will tell!