Zero-trust networking in GCP

Background

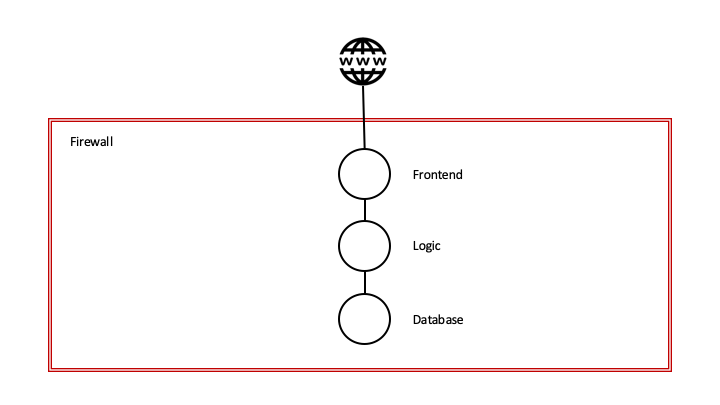

Firewalls and zones have been our primary defense mechanism for years. This model defines a strict perimeter around our applications.

The perimiter is designed to keep potential attackers on the outside, but also to be able to control the flow of data out of the perimiter.

The challenge with this model in a containerized world, is that our applications has become more distributed, which leaves us with more components and thus additional attack surfaces.

Additionally, the attack methods have become more sophisticated, so our safety planning and solutions must be able to address the following: What happens if an attacker is able to breach our perimeter?

Since an application’s architecture is based primarily on an outer defense layer, it would be a relatively simple task for an attacker that is already on the inside to compromise other applications within the same perimeter. Most applications have implemented further safety mechanisms, but those who rely solely on the perimeter are extremely vulnerable.

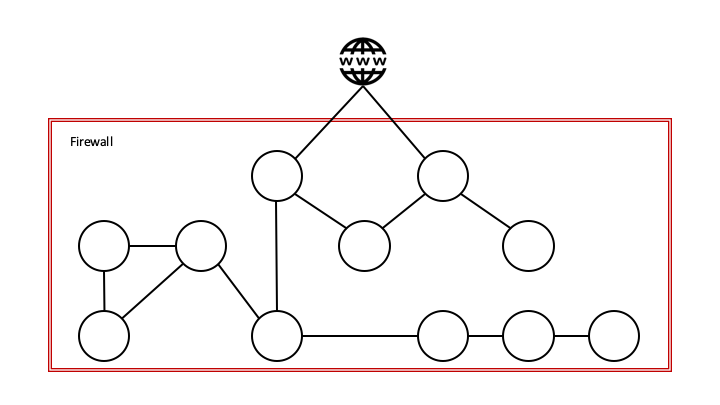

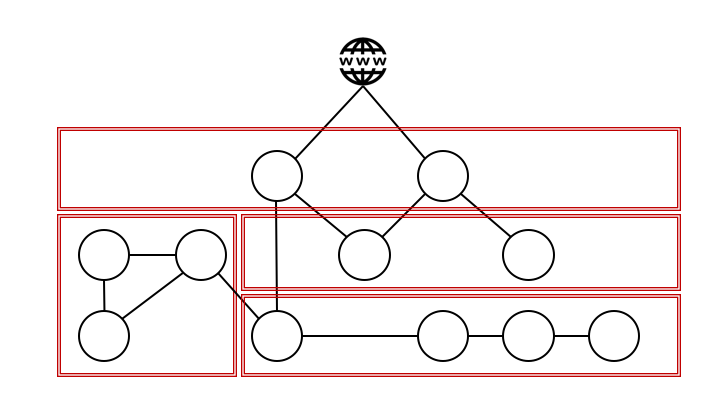

This problem has been addressed using network segmentation; applications with the same safety level and affiliation are grouped together behind separate firewalls.

The challenge remains the same, though; a compromised application could mean a compromised zone.

The next level using this methodology is micro-segmentation and a zone model, where applications and services are grouped in even smaller and more specific zones, givig a potential attacker an even smaller attack surface.

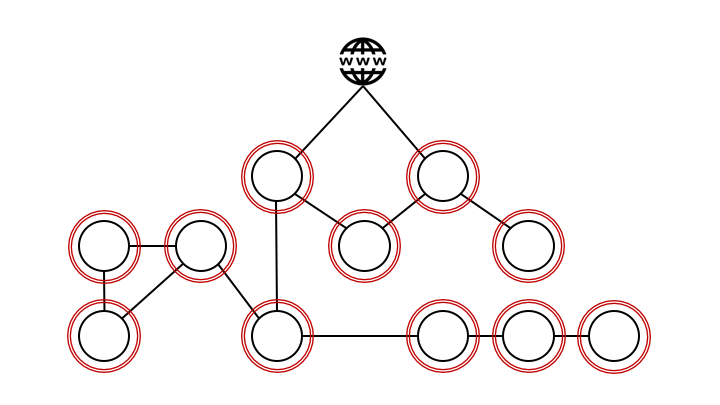

Following this methodology, the inevitable conclusion will be to have a network perimeter around each individual application.

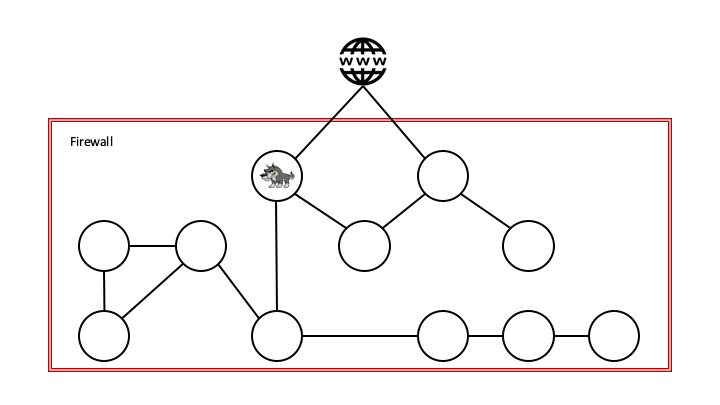

Once each application has its own perimeter, the next thing to address is:

- What if the network itself is compromised?

- Are there attackers on the inside that can listen to or spoof traffic?

We know this is the case on unsafe networks like the Internet, but we can still transfer sensitive data, like bank transactions, safely thanks to encryption.

It is no longer a safe assumption that there are no attackers in our own data centers, our private cloud or in the public cloud, so we should encrypt communication even here.

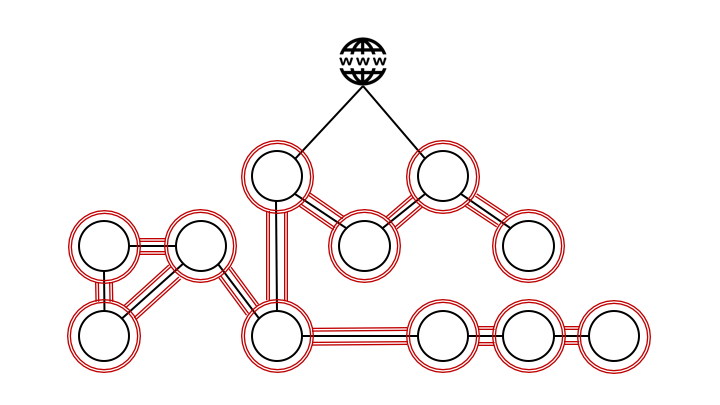

We need to base our transportation security on authentication and authorization between all services, so that we can be cryptographically certain that both the sender and the receiver are who they claim they are. Each endpoint is given a cryptographic identity in form of a certificate to prove their identity. This gives us the ability to make policies and control service to service communication based on identity.

Implementation

Network policies

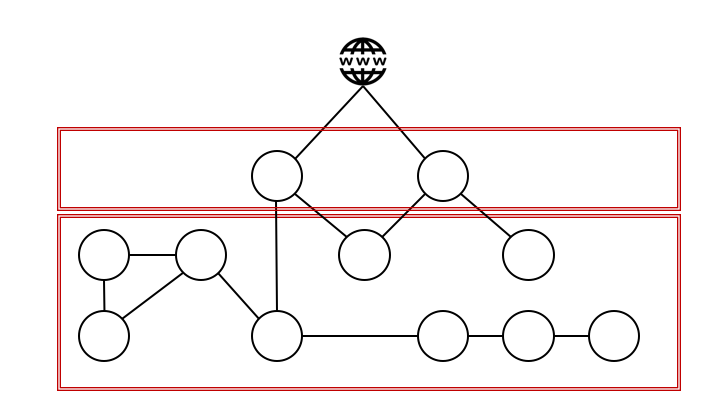

Kubernetes network policy lets us enforce which network traffic is allowed using rules. In essence creating a firewall around each workload Kubernetes pods can be treated much like VMs or hosts (they all have unique IP addresses), and the containers within pods very much like processes running within a VM or host (they run in the same network namespace and share an IP address)

In a team’s namespace, the underlying network infrastructure will deny all traffic both to and from all pods unless explicit network policies have been applied.

Given an example architechture where application a needs to communicate with application b, both appliations will have to apply network policies to allow this traffic:

A allows utgoing traffic to B

kind: NetworkPolicy

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

metadata:

name: allow-app-a-to-b

namespace: default

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: a

egress:

- to:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: b

ports:

- port: 80B allows incoming traffic from A

kind: NetworkPolicy

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

metadata:

name: allow-app-a-to-b

namespace: default

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: b

ingress:

- from:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: a

ports:

- port: 80Istio Authorization Policy

Istio Authorization Policy enables access control on workloads in the mesh and ensures traffic is encrypted using mTLS. In the same way that network policies by default denies traffic on the IP layer, authorization policies will deny traffic on the transport layer by default.

There are no outbound authorization policies, so only application b will have to apply an authorization policy to allow traffic from application a.

Note, though, that application a will still validate the certificate presented by application b before establishing the connection.

apiVersion: security.istio.io/v1beta1

kind: AuthorizationPolicy

metadata:

name: allow-traffic-from-a

namespace: default

spec:

rules:

- from:

- source:

principals:

- cluster.local/ns/istio-system/sa/a-service-account

to:

- operation:

paths:

- "*"

selector:

matchLabels:

app: bAbstraction

Admittedly, adding these features leads to added complexity which in turn demands that developers have an unnecessarily deep understanding of infrastructure functionality. What developers should really be concerned with, is which applications they want to communicate with, and which applications they want communicating with them. Not the minute details of how. Which is why we’ve implemented an abstraction in the NAIS application manifest, that allows developers to do exactly that.

The application spec for application a will generate a network policy allowing traffic from application a to application b

apiVersion: "nais.io/v1alpha1"

kind: "Application"

metadata:

name: a

...

spec:

...

accessPolicy:

outbound:

rules:

- app: bWhile the related application spec for application b will create both a network policy allowing inbound traffic from a, and an authorization policy that authorize applicaiton a

apiVersion: "nais.io/v1alpha1"

kind: "Application"

metadata:

name: b

...

spec:

...

accessPolicy:

inbound:

rules:

- app: a